Prejudice is not a bogeyman. It is not an indicator of innate evil and sadism, tucked safely into less developed times and places that won’t return because lessons have been learned. It is not something you are invulnerable to because you have a brain and you’re your own person. It’s not a novelty. Prejudice is a Venus flytrap that catches you when you’re not paying attention. It’s an attitude that shows itself in fleeting spurts, in average people you don’t expect to see it in. It’s present in family, friends, neighbors, classmates, colleagues, passersby, me, you, everyone. It’s the easy, simple, convenient associations you make between physical makeup and moral behavior to relieve stress, put your mind at ease, make decisions faster, and do the job better. It’s what you feel when you encounter the unfamiliar, when someone argues a viewpoint that you think is watertight. It’s what you shrug off with pathetic excuses, clichéd justifications, kneejerk defense mechanisms, urgent downplaying. It’s a cover for weakness, ambivalence, cowardice, and pain. It’s mostly another way in which humans err.

Last month, the United Kingdom—goaded and brainwashed by far-right, anti-immigration sentiment—voted, in a referendum, to leave the European Union, and in the media, I noticed a slight but significant semantic change accompanying that paradigm shift. Before the vote, it was referred to as “Brexit,” a portmanteau for “Britain’s [then hypothetical] exit”—a savvy new word, a peculiar code, a disyllabic soundbyte that grew more ambiguous and rolled off the tongue easier when the X in exit was altered from [gz] to [ks], a decision that belonged uniquely to Britain and that was Britain’s to make, almost a hip get-out-the-vote command (“Brex it, baby!”) Now, more and more, it is “the Brexit,” as in something that could well be short for “the [voter-approved] British exit”—official, political, dead serious, no longer a potential but a concrete reality, a force to be reckoned with, a choice made and settled, with repercussions far out of Britain’s or anyone else’s control. Listen closely, and you’ll hear the [gz] sound coming back a little in that phrasing, leaving little doubt as to what it is and represents. Even the men behind the Leave campaign—UKIP head Nigel Farage and London ex-mayor Boris Johnson—were so intimidated by the fact of their success, they chickened out of responsibility for it and have now retreated from the Prime Minister-ship. Meaning: they are con men, and their campaign was a shameless ploy, done for money, publicity and provocation, damn the consequences that their nation has to face because of it. Here in the United States, there’s an obvious parallel—more on that in a New York minute.

The Brexit vote seems to have been merely the inception of a long, hot, traumatic summer in what is already one of the ugliest years in recent memory for the world at large, let alone for the West. I can’t name the last day that hasn’t gone by without the news reporting a death toll of some scale. In the time I have been drafting this essay, I have read about a fit of road rage-cum-terrorist attack in Nice—on Bastille Day!—that has killed over eighty; a half-assed coup attempt in Istanbul that has claimed hundreds and that might have produced a military junta far more repressive than Erdogan; and the assassination of three cops in Baton Rouge, likely a retaliation for the murder of Alton Sterling, and an echo of a sniper shooting that downed five cops in Dallas. Battle lines are falling between civilian and state, left and right, centrist and extremist, cosmopolitanism and nationalism, racism and color, Islamism and “infidel”. Those interested in peace are confined to venting their rage on social media, too raw to know how to react otherwise, too numb and unsurprised to figure out a solution. Those interested in prolonging, intensifying and profiting from all the conflict are winning, and the media—maybe unwittingly, maybe deliberately—are fanning their flames for all the sensation they can report.

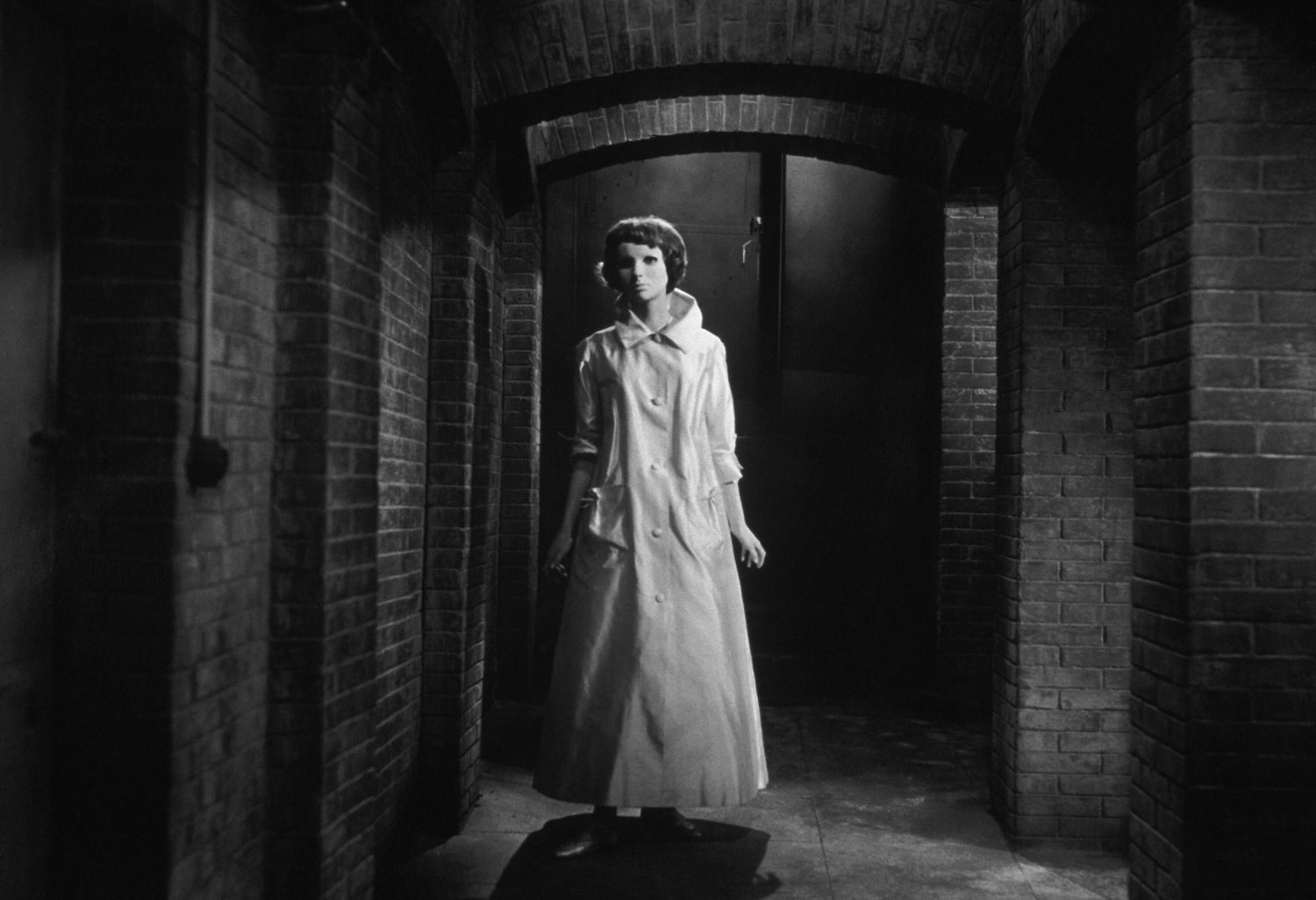

Since Brexit, through this summer, I’ve been thinking much about a British indie film called This Is England, made a decade ago, set during the Thatcher years, and only growing more relevant. It’s about a disaffected adolescent from Sheffield, Shaun (Thomas Turgoose), who lost his father in the Falklands War, and who falls in by chance with a crew of skinheads. Fact, little known to Americans: the skinheads, at least in the British sense, were originally punks who—besides being bald—bonded based on a mutual interest in Caribbean music and New Wave fashion, and whose time was spent apolitically goofing off. Not kidding. Look it up. Shaun comes of age, finds his niche in the crew, and rebels against his frazzled mother in doing so. Then, one Combo (Stephen Graham) is released from prison, reunites with the gang, and uses them as a captive audience to his homilies on England belonging to the English, the welfare state fucking everything up, and the “Paki bastards” hoarding the place. Combo’s rival, Woody (Joseph Gilgun), is a sweet, caring guy, and his charms are what initially draws Shaun in and returns peace and joy into his life—but like too many sweet, caring guys, he lacks Combo’s charisma and psychological acuity and can only watch as Combo exploits the Falklands War to manipulate Shaun and a few others into siding with him. This of course is a microcosm of how the skinheads transitioned into what we think of them as today—namely, fascist-populist goons.

Combo takes Shaun and his protégés to a lodge in a clearing, where a nationalist politico running for office is speaking. He acknowledges that he and his fellow skinheads have been accused of racism. “We’re not racist!” he insists. Ah, but they are racist. Language is ultimately objective; otherwise, it would be too easy for people to excuse themselves for their racial insensitivity by contriving the definition of racism so that it doesn’t include and implicate their actions. On the contrary, too often and too easily, that is exactly what people try to do and what we let people do—because of course, most of us would not like to be labeled racist. (Look at how George W. Bush and his neocon cronies absolve themselves of war crimes just by narrowing the definition of torture to exclude waterboarding—a totally wrong shaggy-dog semantic corruption.) And that is why racial profiling is depicted as an efficient way to manage and discourage crime, when it is really textbook racism because it assumes certain demographics are disposed to crime and does not account for—nor aim to alleviate—the socioeconomic forces that breed crime as a way of life, some of which are reinforced by the state purposely to maintain a racial hierarchy. That is also why immigrants to the U.K. (and the U.S., etc.) who try to bring along their cultural spheres, often including their native tongues, and who don’t assimilate to the liking of the dominant race—regardless of whether they are citizens or not—face demonization, mostly from the right wing. This is racism, beyond dispute. It insists that there is nothing of value worth learning from foreign cultures.

If This Is England has a flaw—besides the abrupt ending—it’s that there’s no developed alternative perspective from any of the Indian and Pakistani persons who become the targets of Combo’s curry-themed verbal and physical taunts, which Shaun imitates and is thus complicit in. It does, however, throw an ambivalence into the proceedings with the presence of a Black proto-skinhead, Milky (Andrew Shim), who provides a conduit to Woody and company’s appreciation of reggae and ska, and who Combo admires because he claims he is English despite his Jamaican heritage—and because he sells Combo pot. Well, really, Combo’s attitude towards Milky is contingent on what shade of Milky’s cultural identity is showing at a given moment. It is obvious that his multiculturalism makes him more well-rounded than Combo will ever be, and Combo knows this, and his envy leads the film to a devastating, powerful climax. The film thus debunks the idea of “having Black friends” as proof that one is not racist. If your attitude towards minorities is conditional in any way, then you’re being racist. The film’s take on race and immigration is thus very postmodern and makes it essential viewing for anyone wondering how racism and friendly associations with people of color can exist in the same person, and how we are all liable to be wrestling with both. The director, Shane Meadows, has continued to follow these characters in three TV miniseries that span through Thatcher’s odious reign; I aim to watch them.

There are those who seek to make society as great as it can be for everyone given the resources, and there are those who are more impelled to compete against one another for a bigger slice. William James’ immortal essay “The Moral Equivalent of War” is instructive in this regard. Man is inclined towards competition; when not offered the diversions of sport, meritocracy and debate, he is more prone to getting suckered into going to war for the petty whims of the ruling class and the military-industrial complex. For the most loathsome of poor sportsmen, it isn’t enough that they win—their opponents must lose, lose badly, and suffer in the process. This entails the lowest among us picking fights with others based on race, sex, sexuality, gender, class, religion, ability, you name it. And so civilization is structured into suffocating hierarchies, and every time those below jostle for a fair share, those on top grow disturbed—spoiled as they are, their equilibrium is thrown off by any notion of societal equality and equity—and they suppress those below to restore homeostasis to themselves. Let it thus be said for the record that if you’re a white, elderly/middle-aged, cisgender, heterosexual, upper/middle-class, neurotypical man who feels the most discriminated-against because of the various social movements struggling for the rights of women, Blacks, Latin@s, indigenous tribes, LGBTQIA persons, youths, autists and Aspies—you’re being a bigot. Sorry, but you are. The protestors you see on media are fighting to survive in ways you’ve never had to do because you’re lucky. One argument in favor of keeping Blacks enslaved before the Civil War was an insane phobia of White enslavement by Blacks. So you see, pro-slavery Whites were aware of the trauma of the system they were perpetrating, but they kept perpetrating it because capitalist doctrine convinced them that they and the Blacks were locked in a zero-sum game, and racial coexistence was a myth.

That’s the horn that Donald Trump is tooting. If This Is England and Brexit show a trend of English nativists fighting for a monopoly over what England is and what it ought to be—a monopoly in which foreign points-of-view mean less than jackshit—then Trump and his lemmings have thrived on a fantasy of an ideal America defined and bleached to their uncompromising preferences. “Make America Great Again,” they say, meaning that there was a time when America was great, after which we lost our way—but when? The Reagan years? The postwar era? The Roaring Twenties? The Gilded Age? No one’s bothered to specify. All I know is that Trump is looking to the past, going backwards, and reversing progress to the point where straight old wealthy white Protestant men reign supreme once again. Mexican immigrants? Trump wants them to become not just American citizens but Americans, just as Milky is only any good in Combo’s eyes when he’s English. Whoever doesn’t abide gets deported. The same will go for Muslim immigrants, whenever Trump plans to allow them in (as if). This is racism, objectively. I didn’t think such racism had any appeal anymore. I thought Trump’s campaign would crash and burn in record time. Alas—Trump has developed a terrifying ethos. Everything said about him, good and bad, seems to benefit him. Every iota of media attention gratifies him. Those who have voted and plan to vote for him show a streak of nihilism and hedonism. They don’t care about building a better nation. They care about winning, about beating the folks they hate—the more destruction, the better. It’s all a reality TV contest to them. They’d just as soon vote Kim Kardashian’s callypgous body into the Oval Office.

Maybe you, reader, are a Trump supporter and would like to insist you’re different. Maybe you lucked out of a job because of cheap labor. Maybe you’re genuinely anti-establishment, anti-incumbent, and think that the media at large want to uphold a status quo and rail against Trump out of panic. Maybe you just don’t like being “politically correct”. I understand. And because I’m committed to bettering society and promoting equality and equal opportunity—and not to competition for its own sake—I’ll reach out to you. I voted for Bernie Sanders. I used to detest Hillary Clinton because I believed Juanita Broaddrick when she said that Bill Clinton raped her and Hillary tried to threaten her into silence. I have written as much on this blog. I believe rape survivors as a matter of principle. As it turns out, Broaddrick has endorsed Trump—never mind his track record of gross misogyny, and the fact that he himself has faced down his own sexual misconduct accusations (which I believe). She has also allied herself with Kathleen Willey, a fellow Bill accuser and discredited conspiracy theorist who has implied that Bill arranged for her husband to be murdered on the same day of her alleged assault, and that Vince Foster was murdered. Not to mention, her Twitter feed has become a scroll of recurring, glib anti-Clinton potshots—trivial memes and such.

Individually, these might be lapses of poor judgment; together—along with the multiple issues of Broaddrick’s account (she doesn’t remember the date, she’s been inconsistent on whether Hillary or anyone threatened her, her witnesses have a conflict of interest, et al.)—they add up. One thought I’ve had is that maybe she consented after Bill gave her the old line about how mumps made him sterile, and then heard about Chelsea’s birth a couple years later and felt deceived—but why wouldn’t she clarify that? Where are her standards? Even if I never know what really happened (I won’t), this is something I feel I need to get right. If I say Bill Clinton is a rapist and I’m wrong, I falsely accuse an innocent and insult genuine rape survivors. If I say Juanita Broaddrick was not raped and she was, I deepen her trauma. I’m fucked either way. Right now, I’m going to trust my instincts. It is worth repeating the cliché that the medium is the message. Broaddrick isn’t airing her message through a feminist-activist lens; she’s doing so through the media of puerile right-wing Clinton-bashing, which toys with the truth to get Republicans voted into office where they can push a bluntly anti-feminist agenda. The case for Bill Clinton being a rapist and Hillary being an enabler is very doubtful, to say the least. Anything I have stated in the past to the effect of otherwise, I hereby rescind.

What I’m trying to say is: I’ve changed. In an election cycle dominated by proud voters who claim their minds are made up, who grow more stubborn with each reasonable rebuttal to their positions, I—a fervent pseudo-socialist Sandernista—have warmed up to someone I once sneered at for being a pro-fracking, pro-TPP Wall Street sympathizer with ties to Henry Kissinger and Jeffrey Epstein. So just maybe, you could change, too. Take a step back. Look at the bigger picture. Pick pragmatism over tenacity. Listen to all the viewpoints. Be humble, realize where you might be and have been wrong, and admit it. Be willing to ask questions and have reservations, but don’t expect the politicians you vote for to be perfect and align with you on everything. That said, the question remains: would a vote for Hillary make me complicit in the missteps of her presidential term, or would it make me a stakeholder in her presidency who is more entitled to criticize her for stuff such as her reaction to the 2009 coup in Honduras than someone who sat out the vote? It’s up for debate. Here’s the bottom line, though: I want the Supreme Court to go left. I want Citizens United overturned, and I want to keep abortion, gay marriage, affirmative action, the right to privacy and public unions safe for the next generation. I want to see legislation on climate change and gun control passed, I want college to be affordable, and I want a leader who doesn’t rely on the superficial appeal of charisma to win over constituents—in that way, Hillary Clinton’s lack of charisma turns out to be arguably her best asset.

Face it, ‘Merica: most of the attacks on Clinton are either misogynistic boilerplate or hypocritical. Benghazi? She showed clear contrition for her negligence when that happened, and the late Ambassador J. Christopher Stevens’ family (not unlike Vince Foster’s family) has stated that they do not want his death politicized. And yet, she can’t catch a break from the fear-mongering party that exploited the trauma of 9/11—which happened on their watch, after some very clear warnings—to create phantom WMDs and get national support for a half-assed vigilante coup in Iraq that destabilized the Middle East, worsened anti-American sentiment everywhere, and led directly to the rise of the Islamic State. Her emails? FBI director James Comey has admitted that his strong words against her were politically incentivized (read: dishonest). Bill’s infidelities? Folks, I am fairly certain that Hillary and Chelsea have taken him to task for that behind closed doors. The way things stand now, I intend to vote for Hillary Clinton in November. If anything goes wrong, I reserve my right to tell my fellow Democrats that they should’ve voted for Sanders. (I don’t mean to perpetrate the thought that this election is a two-party either-or decision. Jill Stein is great, and I actually agree with Gary Johnson on quite a few things. In a two-party system, the success of third parties depends on the classic game theory debacle of whether enough people plan to vote for a third party to make it worth risking your vote on said third party. Polarized as the nation is right now, I myself am not counting on it. If the Libertarian Party takes away enough votes from Trump, I’ll applaud them for it.) I no longer think that four years of Hillary Clinton would be unlivable; her staffers have given her universal praise and are baffled by the negative media perception of her. I will never not think that a Trump presidency would cause unmitigated global catastrophe. Alas, I’m confident Clinton will prevail. That doesn’t mean we as voters should be complacent, though. The threat of Trump is concrete, and he has already badly damaged the nation’s fabric and reputation.

I condemn Donald Trump entirely. I condemn his blatant disregard for the First Amendment guarantees of free speech, a free press, and freedom of religion that are what truly make America great, if anything. I condemn his stated intent to commit war crimes such as killing the families of terrorists, regardless of their innocence. I condemn his propagation of conspiracy theories such as “Obama was born in Kenya” and “vaccines cause autism.” I condemn his intelligence-insulting lies, his incessant positional flip-flopping, his constant dodging of valid inquiries, and his evasion of personal responsibility. I condemn his emboldening of anti-Semites, the Ku Klux Klan, and other figures in the insidious alt-right, whom he has refused to disavow likely because he perceives them as a valuable voter bloc. I condemn his misogyny, his bigotry, his glibness, his incompetence, his confidence schemes, his abusive business and legal practices, his narcissism, and his cult of personality. I condemn that he has singlehandedly brought to the U.S. the same dangers the far-right has presented to the U.K., France, the Netherlands, Italy, Germany, Austria, Hungary, Scandinavia, Russia, Ukraine, Brazil, Israel, and the Philippines. I condemn his call for a clash of civilizations, and for greater arms in anticipation of them. I condemn his noncommittal attitude and the implications he’s given off that it’s all a long con and he’s planning to forfeit his presidency and leave us stranded with lousy Hoosier Mike Pence should he win. More than anything, I condemn the culture of anti-intellectualism that he promotes and thrives on.

Trump supporters: how do you dare take pride in gaslighting and not caring about facts as a way of defending yourselves from being proven wrong? Please just take one minute to ask yourselves: do you really think that undocumented immigrants are the one thing preventing you from getting hired? If a minority becomes your coworker, what is it going to take for you to believe that (s)he got to your level on merit and not on affirmative action? Are you voting anti-establishment for its own sake? How does “Black Lives Matter” translate into “Only Black Lives Matter”? How can you say that Trump isn’t talking about all Mexicans and Muslims—or even Mexicans and Muslims in general—and that Quentin Tarantino is talking about all cops when he says, “I must call a murderer a murderer”? When you say the ends justify the means, have you failed to acknowledge those who have been traumatized by the means? And do you really think that political correctness is a magic wand that licenses you to say racist things while excusing yourself from accusations of racism, or to support racist policies under the conviction that what’s easy is what’s right and the-ends-justify-the-means? Freedom of speech, like all freedoms, comes with responsibility. Language is powerful, it can harm, and you are responsible for your use of it, not least because language can become law—what is law but language?—and law has severe impact. When people grieve over a family getting slaughtered because a relative of theirs joined the Islamic State, through no fault of their own, will you dare blame them for being too politically correct?

If this essay convinces merely one person to not vote for Trump, I will consider it a success.